Some people pruned their networks, focusing on only the most important family and friends. Others lost friends through reduced recreational and community activities, falling out of the habit of socialising, and shifting to more digital interaction.

Roger Patulny, University of Wollongong

As we resume our social lives after strict COVID restrictions have lifted, many of us are finding it’s time to take stock of our friendships.

Recent research I’ve been involved in found friendship networks were shrinking in Australia during COVID lockdowns.

Some people pruned their networks, focusing on only the most important family and friends. Others lost friends through reduced recreational and community activities, falling out of the habit of socialising, and shifting to more digital interaction.

As we start to re-engage, the obvious question is – how do we get our old friends back?

Lonely after lockdown? How COVID may leave us with fewer friends if we are not careful @MarleeBower @TheMatilda_USyd @rpatulny https://t.co/3qA4dko2Q3 via @ConversationEDU

— Mark Scott (@mscott) October 11, 2021

A 40-year friendship ends badly and publicly, leading to a forensic examination of what it means to have and be a friend. https://t.co/YBLX5qH7Wo

— The Conversation (@ConversationEDU) September 19, 2019

We might also ask ourselves – which friends do we want back?

Read Also: Guide to Starting Conversation with localities in Australia

Which friends do we want?

There’s no one answer here – different people want different things from friends.

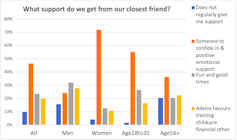

Data I have calculated from the 2015-16 Australian Social Attitudes Survey show the main form of support received from close friends in Australia is:

- primarily, having a confidant who provides emotional support

- followed by fun and good times

- and then, favours and advice of various kinds.

These results vary by background and life stage.

Women are much more likely to have a confidant who provides emotional support as their closest friend. Men are more likely to have friends who provide fun, good times, favours and advice – or else no regular support at all.

Younger people are more likely to have a confidant, emotional support, fun and good times. Older people, aged over 56, are slightly more likely to receive favours and advice, and are much more likely to lack a close supportive friend.

Data: Australian Social Attitudes Survey 2015-16/Roger Patulny, Author provided

These results are indicative of what different people get from close friendships, but may not represent what they want or need.

The close confidants women report as friends may well alleviate emotional loneliness, which is defined as the absence of close attachment to others who provide strong emotional support.

However, it may still leave them with social loneliness, or the feeling of lacking quality, companionable connections with friends.

Conversely, male camaraderie built around fun, activities and mutual favours may alleviate social but not emotional loneliness.

Emerging evidence suggests emotional loneliness has a stronger negative impact on well-being than social loneliness, so it’s important for everyone to have someone to talk to for emotional support.

We still need a variety of approaches and goals to suit different friendship needs nonetheless.

Beating social loneliness

The first way to reduce social loneliness is to reach out to those we already know, now that we can.

We can message old friends, organise get-togethers, or start new conversations and activities with everyday contacts including colleagues, fellow students, regulars at the local club or cafe, or neighbours.

That said, reconnecting may now be impossible or undesirable for several reasons. These can include physical distance, changed life circumstances, different interests, intractable arguments, or a masculine aversion to initiating contact.

In these cases, we can join, organise, invite others, and connect with new social and community groups. Better groups tend to run regular activities that genuinely reflect members’ interests and input. Generic groups that meet sporadically are less effective.

Some people may benefit from joining support groups designed for people subject to stigma based on identity or life events, such as LGBTQI or health recovery groups.

Some groups help deal with the stigma of feeling lonely. This includes shared activity groups where people talk “shoulder to shoulder” rather than face to face, such as Men’s Sheds.

Missing a friend you’ve fallen out with? Here’s how to restore a relationship https://t.co/dgRUCjVbrG

— ABC News (@abcnews) May 9, 2020

Groups focused on education, shared discussion, or exercise are particularly good for friendship and alleviating loneliness among older people.

While online options abound for connecting, it’s important to avoid activities which increase loneliness, such as passive scrolling, unsolicited broadcasting, or escapist substituting of digital communities for physical ones.

Interactive online contact and online groups that help us organise in-person catch ups (such as WhatsApp, Facebook or Meetup) are more effective.

Beating emotional loneliness

To beat emotional loneliness, the focus should be on deepening existing relationships.

It’s essential to spend high quality, meaningful time with a few good quality friends (or even one).

It might mean repairing damage, and apologising in a considered and respectful manner if you did or said something wrong.

Sometimes it just requires the effort of checking in more regularly. Organisations like RUOK provide sensitive, step-by-step suggestions on how to do this.

Online contact and videoconferencing can help maintain intimate partner and family connections, as it did during lockdown. It’s particularly helpful for older people and migrants, but less so for younger people already saturated in online social media connections.

Read Also: How to make friends in Australia

Some people may also need help from a professional psychologist, counsellor, or support group to process increased social anxiety, particularly after COVID lockdown.

Such support can reduce emotional loneliness by helping us process social situations more positively and be more realistic (and less anxious) about our friendship options.

Ending wrong or ‘toxic’ friendships

In reflecting on our friendships, we may decide to end any that have become particularly toxic.

Where possible, we should be kind, explain this, and avoid ghosting, as this can be highly traumatic to those who are ghosted and de-sensitise us to others’ feelings if we do it regularly.

A 40-year friendship ends badly and publicly, leading to a forensic examination of what it means to have and be a friend. https://t.co/YBLX5qH7Wo

— The Conversation (@ConversationEDU) September 19, 2019

Before doing so, we should be careful we don’t just need a break to rebuild energy and habits of interactions.

We should be especially careful with ending long-term friendships. Quality relationships take time, shared history, and involve natural ups and downs – especially in a pandemic. We should look to renegotiate rather than end them wherever possible.

Take time, and seek counselling or another friend’s advice. Since listening is key to friendship, maybe ask yourself – have you heard everything they’re trying to say?![]()

Roger Patulny, Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.