The federal government’s decision to lift Australia’s permanent migrant intake from 160,000 to 195,000 this financial year, which it announced at the jobs summit,

Brendan Coates, Grattan Institute and Tyler Reysenbach, Grattan Institute

The federal government’s decision to lift Australia’s permanent migrant intake from 160,000 to 195,000 this financial year, which it announced at the jobs summit, has been applauded by business leaders and premiers.

But by itself, lifting migration will do little to fill widespread skills shortages, partly because three in every four migrants granted permanent visas are already in Australia.

Even if the larger intake succeeds in bringing in more people from overseas, more migrants will mean a bigger economy, which will itself increase the demand for workers. And it will mean having to build more homes.

But it should boost the budget’s bottom line. Grattan Institute modelling suggests an ongoing increase in the annual permanent intake of 195,000 would boost federal and state budgets by up to A$33 billion over the next decade, depending on exactly which streams the extra visas are allocated to.

The decision to commit $36 million to help work through the backlog of 900,000 outstanding visa applications is welcome – although it is likely even more resources will be needed to get the program back on track. [ads2]

Sensible easy calls

The government has also extended by two years the period international students studying in-demand degrees can remain in Australia after graduation: from three years to five years for masters graduates, and from four years to six years for PhD graduates.

But the bigger challenge is improving the poor employment outcomes of the international graduates who are already here.

Despite their qualifications, a quarter of recent graduates are either unemployed or not looking for work. A further 17% work in low-skilled occupations in retail, wholesale and hospitality. Most earn no more than working holiday makers.

The government also extended the relaxation of work rights for international students – traditionally capped at 40 hours a fortnight – until 30 June next year.

But having made these easy calls on areas where consensus emerged at the summit, the government faces two tough choices.

Challenge 1: lifting the income threshold

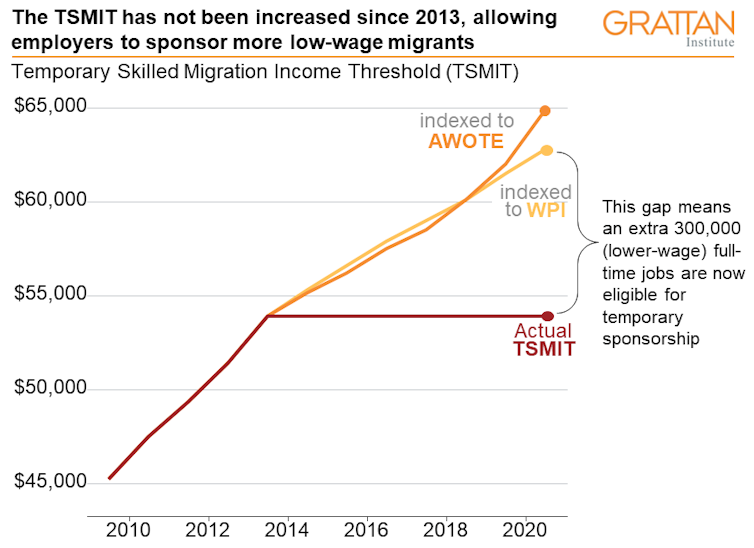

The immediate challenge will be settling the debate over raising the Temporary Skilled Migration Income Threshold (TSMIT), which puts a floor under the wage at which employers can sponsor workers via the temporary skills shortage visa.

The threshold hasn’t been increased since 2013, and at $53,900 a year, has fallen in relative terms to the point where it is lower than the wages earned by 80% of Australian full-time workers.

Read Also: Australia increased Post Study Work Visa length: know what it means to you

Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee Inquiry into the Effectiveness of the Current Temporary Skilled Visa System in Targeting Genuine Skills Shortages. (2019), ABS Average Weekly Earnings and ABS Wage Price Index

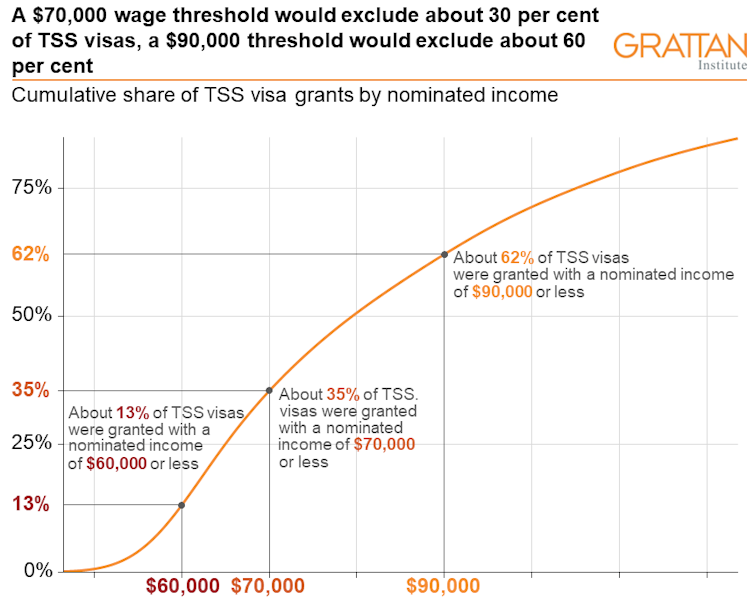

Unions want the threshold raised to $90,000.

The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry wants it lifted to just $60,000.

The Grattan Institute has suggested a threshold of $70,000 – roughly where it would have been if it had been indexed to wages over the past decade.

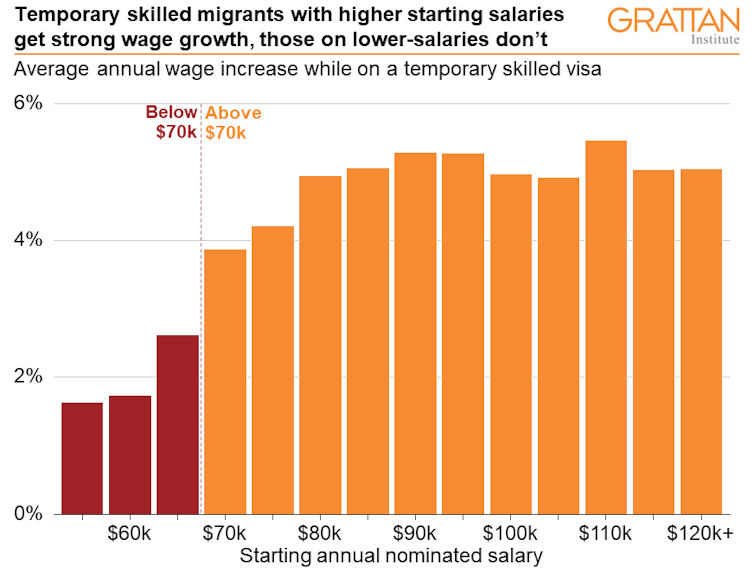

Our research suggests skilled migrants who earn $70,000 on arrival get few or no pay rises, whereas those who start out on more than $70,000 tend to get big pay rises – more than 5% a year on average – over the course of their stay in Australia.

Lifting the threshold to $90,000, as the unions propose, could cut out many of the younger skilled workers who form the bedrock of permanent skilled migration.

Temporary skills shortage visa-holders are, on average, much younger than the typical Australian worker, and start out earning less.

A $90,000 threshold would knock out about 60% of recent temporary skills shortage visas granted, compared to 35% for a $70,000 threshold.

Grattan analysis of ABS Multi-Agency Data Integration Project 2021

Challenge 2: better pathways to permanent residency

The second big challenge is to provide better pathways to permanent residency for temporary migrants, including temporary skilled workers and international students, as the federal government has signalled it wants.

Australia offers only a fixed number of permanent visas each year. In contrast, Australia’s temporary migrant intake is largely uncapped, except for limits on working holiday visa grants for some countries.

Simply put, it’s not possible to run an uncapped temporary migration program and a capped permanent program, and offer temporary visa-holders a pathway to permanent residency. Something has to give.

Resolving these two challenges will loom large in the review of the Australia’s immigration system announced by Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil during the summit, which is due to report by the end of February 2023.![]()

Brendan Coates, Program Director, Economic Policy, Grattan Institute and Tyler Reysenbach, Research associate, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.